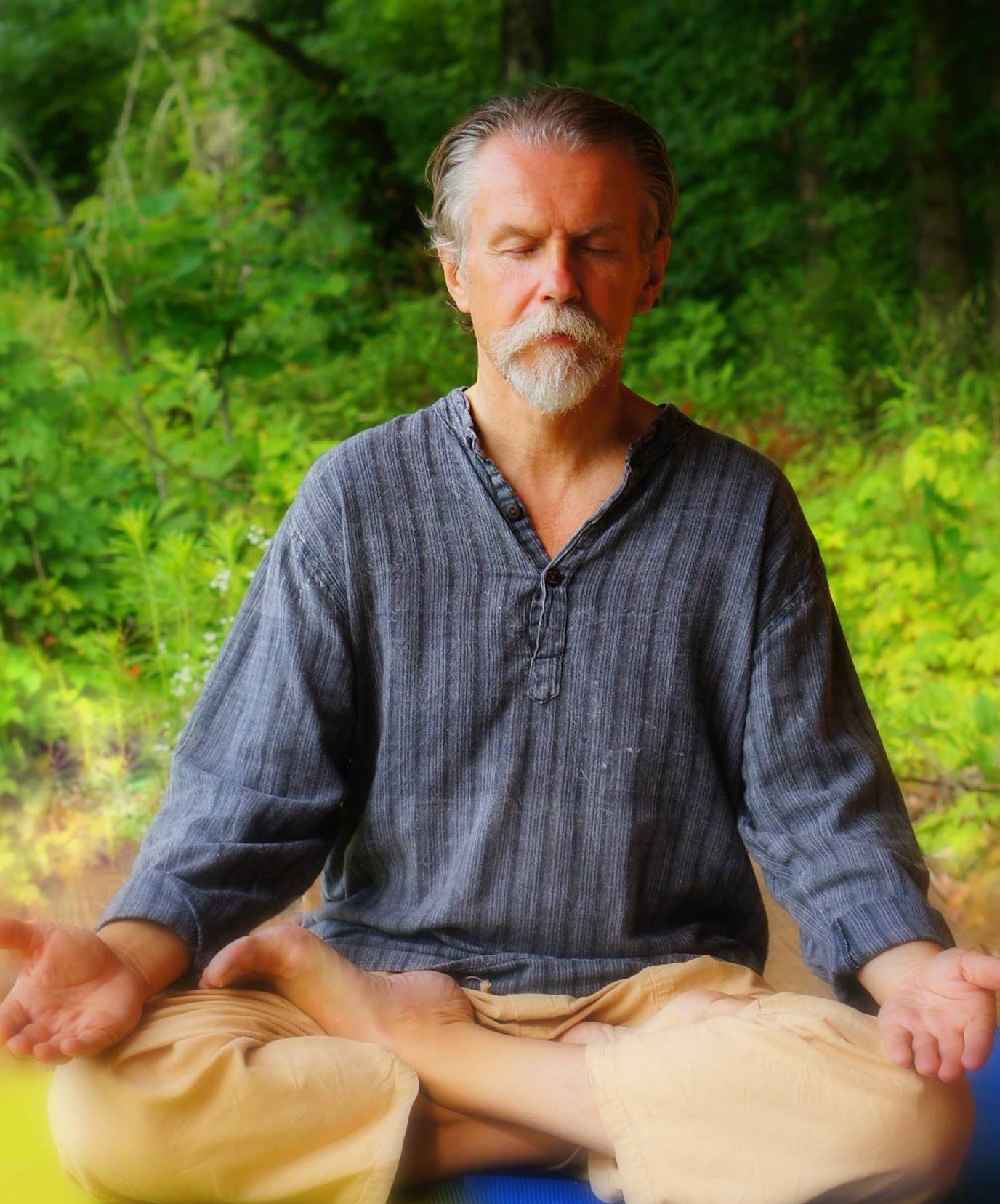

Ramesh Bjonnes: The Elizabeth Warren of Yoga & Tantra ~ Chris Kiran Aarya

A review of Ramesh Bjonnes’ new book: Sacred Body, Sacred Spirit: A Personal Guide to the Wisdom of Yoga and Tantra.

In 2008 as the U.S. financial system was in teetering on the edge of disaster, a fearful and confused public was not able to understand the complexities of why and how we had gotten into such a mess. The complex and tangled web of credit default swaps, derivative markets and unprecedented risks the banks had taken were not fully appreciated by the public until Harvard Professor Elizabeth Warren came along to explain them in language lay persons could understand.

In 2008 as the U.S. financial system was in teetering on the edge of disaster, a fearful and confused public was not able to understand the complexities of why and how we had gotten into such a mess. The complex and tangled web of credit default swaps, derivative markets and unprecedented risks the banks had taken were not fully appreciated by the public until Harvard Professor Elizabeth Warren came along to explain them in language lay persons could understand.

Her ability to explain complex concepts to a broad audience changed the national conversation in a positive direction as more people were empowered with levels of knowledge they had been previously unequipped to access.

While in the Western world we’ve had a number of intellectual heavyweights on yoga and tantra such as Georg Feuerstein and Edwin Bryant (to name a few), we’ve never really had an “Elizabeth Warren of Yoga and Tantra” until Ramesh Bjonnes began writing for elephant journal in 2010.

In the name of full disclosure, I must admit that I’ve been a fan of Ramesh since I began reading his column and I often turned to him for help when seeking to make the authentic more accessible in my own teaching.

In reading Sacred Body, Sacred Spirit, I quickly recognized Ramesh’s ongoing intention to dispel the idea that tantra is a branch from the tree of yoga but rather the reverse that yoga’s roots lie within Tantra itself. What also stands out clearly is his intention to bring living tantra to a much broader audience.

Within the first pages of the book, he discusses the ideas of Western and Indian yoga scholars who believe that yoga comes solely from the Vedic tradition (brought in either by either Aryan invaders or that the Vedic Aryans were already native to India)—a concept Bjonnes refers to (and rejects) as the “One River Theory.”

Ramesh then offers historical, archeological and genetic evidence to support his own “Two River Theory”—the idea that the history of yoga is actually a blend of the Tantric and Vedic traditions of India.

He continues to weave this idea throughout the book illustrating how the Vedic and Tantric cultures form two worldviews; the former focused on the ritualistic and religious quest for fierce control while the latter is mainly empirical and spiritual and aimed at alchemical transformation.

And despite these seemingly different approaches, he collects and examines broad aspects of yoga and tantra from numerous traditions to show not only how they are related, but as he concludes, that they are essentially the same and perhaps are just seen from a different perspective. This is particularly clear in the chapter Tantra and The Yoga Sutras: If Patanjali had Been A Woman in which he examines Nischala Joy Devi’s book The Secret Power of Yoga. In that book, she applies her heart, not just her head, to interpreting the Yoga Sutras with the results sounding more Tantric than Vedic.

For example, Georg Feuerstein’s well-respected translation that “Yoga is the restriction of the fluctuation of consciousness” is held out as an example of the disciplined (and more literal) Vedic approach. Conversely, Nischala Joy Devi’s translation of the same passage reads “Yoga is the uniting of consciousness in the heart”—a more Tantric interpretation of the same original words.

But not to dishonor or dismiss the Vedic interpretation, Bjonnes offers the words of his teacher Anandamutri (who interprets the Sutras much like Feuerstein) that “Patanjali meant that a yogi must suspend his or her mental tendencies (vrittis) in order to find peace and thus, experience the goal of yoga.”

And no book about tantra would be complete without several discussions of the cosmic consciousness of Brahma, composed of Shiva and Shakti. What I particularly appreciate about Ramesh’s approach to discussing Shiva and Shakti is that he does it in a way helps to steer people away from identifying primarily with one or the other (often men to masculine Shiva and women to feminine Shakti) but rather he offers a constant reminder that the two are inseparable because they are one.

And no book about tantra would be complete without several discussions of the cosmic consciousness of Brahma, composed of Shiva and Shakti. What I particularly appreciate about Ramesh’s approach to discussing Shiva and Shakti is that he does it in a way helps to steer people away from identifying primarily with one or the other (often men to masculine Shiva and women to feminine Shakti) but rather he offers a constant reminder that the two are inseparable because they are one.

In the process, he also offers practical reminders of how to stay aware and connected to the ever-present source, requiring discipline, not indulgence—in both deep practice and deep love while also staying engaged in the world.

In keeping with his intention of offering a book about transforming our ordinary life experiences into sacred ones, he not only discusses broader aspects of yoga and tantra but he also delves into some details on everything from dispelling a myth about when women were allowed to practice yoga, to why Tantric love is not just about sex, to why we chant om at the end of yoga class. Its only fitting that since some refer to Tantra the “yoga of everything” that this book seems to be about just that: everything, and how it is connected to everything else.

Throughout the book, Ramesh’s discussions can be soaring threads of inspiration but they are also laced with much plain spoken language and often blunt criticism, such as when he refers to the Christian belief in the virgin birth as “irrational hogwash.”

But lest it appear he is picking on any one path or tradition (even science itself), he tries to apply the same rigor to each one being discussed as he turns over many stones the average reader may not have thought to examine. In this sense, the book feels like sitting around the fire with Ramesh on a dark night as he explains each concept and answers questions in a way everyone in the group can understand.

While just under 200 pages, Sacred Body, Sacred Spirit is like a rich mental and spiritual brownie—best enjoyed by taking small bites and allowing them to sink in rather than gulping it down in one sitting.

It seems that today we are blessed with a number of thinkers and teachers on the subjects of yoga and tantra who seek to fill the role of the bearded sage in the back of the cave, guiding dedicated seekers deeper into the journey of their practice.

I’ve long believed that what we need more of are thinkers and teachers who place themselves at the mouth of the cave of knowledge, inviting people inside by making the authentic more accessible and thus enable more people to find the path of Tantra and Yoga.

In Sacred Body, Sacred Spirit, Ramesh Bjonnes fills both of these roles quite well.

This review was originally published in 2012 on Elephant Journal